Clipping and Headroom: The secret to lively, dynamic mixes

9 Jan 2026

They sound like hipster grooming salons… but a basic knowledge of both makes your life easier and your tracks better

Music recording and mixing is a magical pursuit. It’s how we turn our ideas into the best versions of themselves. But as fun as it is to transform multitrack sessions into living, breathing songs, there are some boring rules to (mostly) not break. Luckily, they actually make studio life easier and more creative.

The most dull-but-useful of them relate to clipping and headroom. In other words, what happens when audio signals are too strong… and the way we take control of that.

Clipping can be a thorn in the side or the secret sauce to make a mix pop, an unwanted playback error or the defining sound of an era. Headroom, meanwhile, gives you room to express yourself with creative processing and mixing.

This article covers everything you need to know, from headroom in digital recording, mixing, and mastering, to the genre-defining, tone-shaping uses of clipping.

It’s all very straightforward, and equipped with this knowledge – plus free track analysis from Mix Check Studio – you can craft richer, more dynamic mixes.

Clipping? Headroom? What are they?

In layman’s terms, clipping is what happens to an audio waveform when you drive the signal through an analogue or digital signal path at too high a level. It changes the sound. Sometimes we want this. Sometimes not.

Think of headroom, then, as the space you have to raise a signal level without clipping occurring.

To properly understand both, let’s recap some basics.

Waveforms and peaks

All sound travels in waves. And all audio signals – both analogue and digital – are expressed by corresponding waveforms.

Waveforms

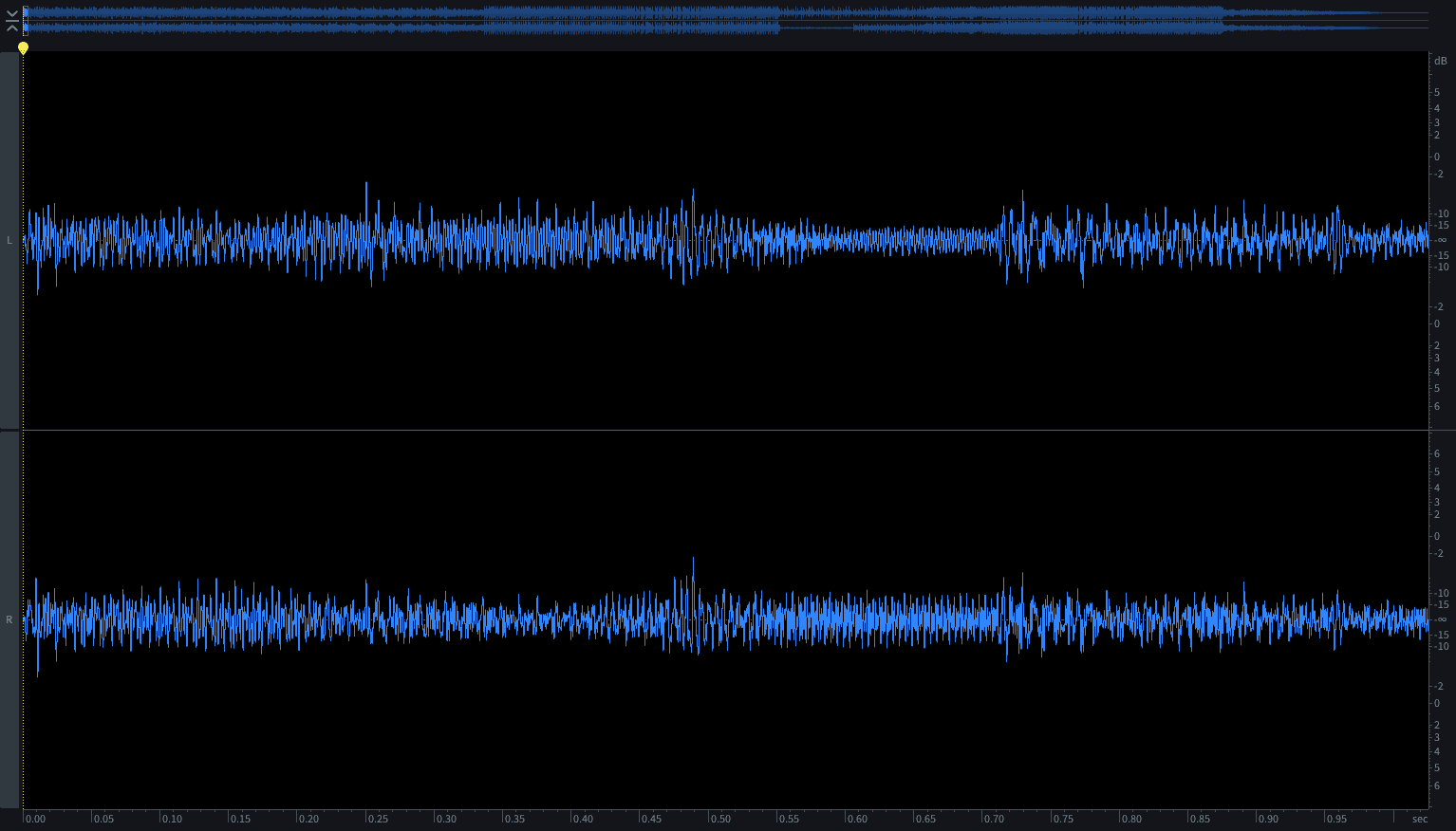

Here is the waveform for the first second of Daft Punk’s Digital Love.

The shape and cycling speed of the waveform dictates tone and timbre (i.e. how the resulting audio will sound) while the height determines the level of that sound.

Now compare these two.

They’re different heights but have the same shape, and cycle at the same speed, so they will sound the same, even though the first is quieter.

As we’ll see, both the shape and the height relate to clipping.

Peaks

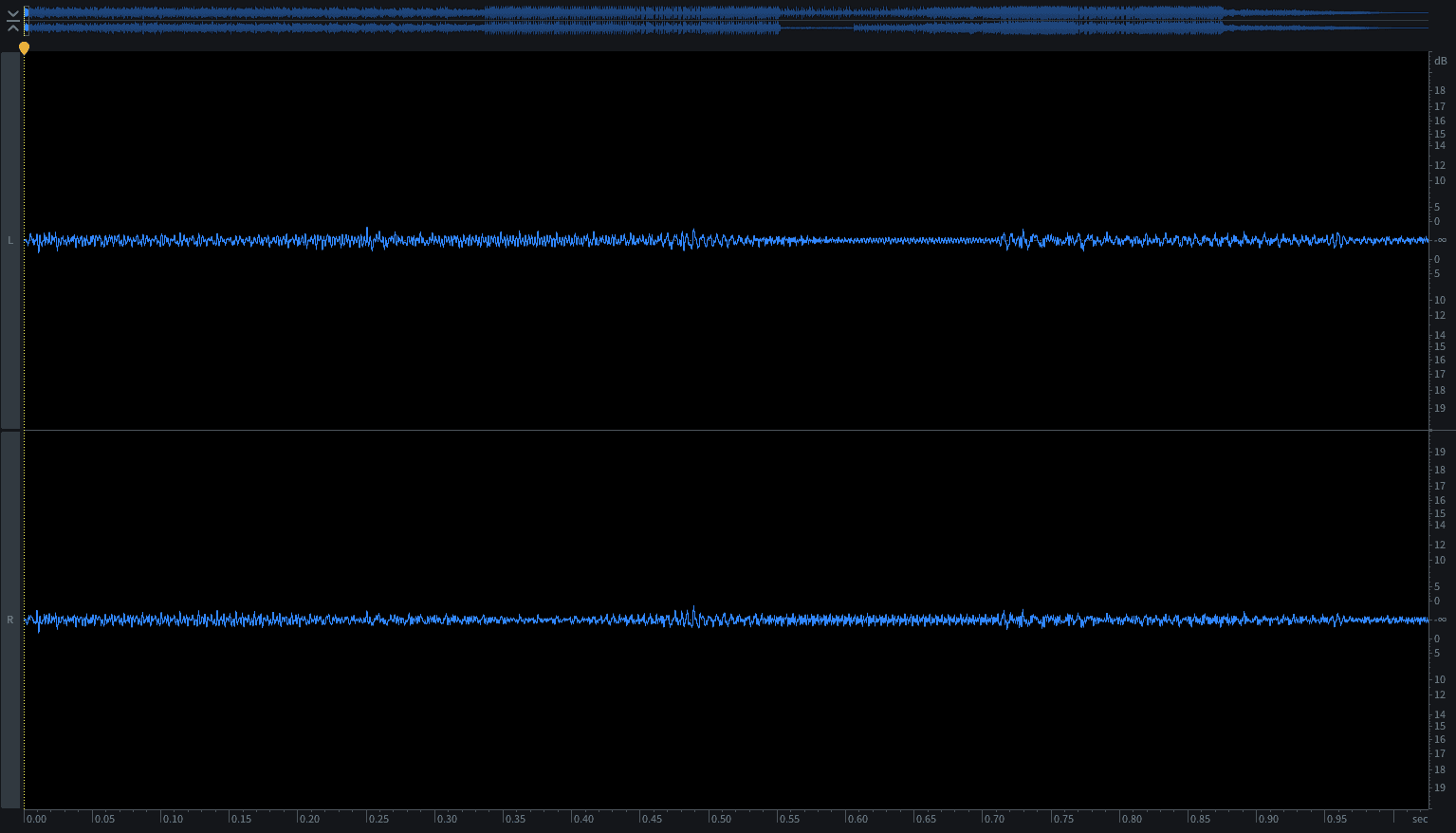

‘Peak’ refers to the highest value for a waveform in a recording/audio signal. Take a look at the audio file below.

The peak is the highest value reached, and in digital audio systems is expressed as a dBFS value (see A Simple Guide to Loudness and Metering for more on dBFS).

The peak for the kick drum sample above is -1dBFS (1dB below 0dBFS).

What is clipping?

Let’s expand our earlier definition a bit, armed with our new knowledge about waveforms.

To be precise, clipping is what happens when the signal strength (level) of an audio signal exceeds the ability of the system to accurately maintain the shape of the waveform.

At some point in any system, increasing the signal level will alter the shape of the waveform and, therefore, how it sounds.

Peaks, then, are an integral part of clipping.

Analogue clipping vs digital clipping

The first thing to understand is the difference between clipping in real valves and circuits and clipping in digital systems.

In analogue systems, clipped waveforms are organically squashed. The dynamic range will be squashed, increasing the apparent loudness (see A Simple Guide to Loudness and Metering), but there will also be increasing analogue distortion. Consequently, while not ideal for clean mixing or mastering, analogue clipping circuits are actually a much-used tool for adding harmonics to signals.

Digital systems, however, do not naturally generate this squashing effect. Without intervention, they simply slice off the top of the waveform, often introducing a range of horrendous unharmonic distortion when converted back to sound.

Digital systems, therefore, often employ protection algorithms to prevent the horrible audio artefacts that would otherwise result. But even at their best, they’re designed to be as transparent as possible. Pushed too far, they will start to break down in unmusical ways, rather than adding pleasing harmonics or progressive squashing. So there’s usually nothing to be gained (pun intended) by overloading a digital system.

What happens to the sound of clipped audio?

Clipping can have a variety of effects on audio signals.

Examples include:

– loss of bass frequencies

– distortion/saturation

– damaged transients

– crackle, clicks, inharmonic distortion (digital systems)

– reduced dynamic range

– smooth rounding of transients

Some are positive, some negative, and some can be either, depending on the context.

Bad clipping – things to avoid.

When we talk about clipping, we’re usually talking about it as something that happens at the input stage of a device.

Clipping at the Analogue-to-digital converter stage can be particularly nasty. That hard 0dBFS limit means that without protection algorithms, clipping would sound less like creative harmonic distortion and more like the Devil himself spraying a jetwasher directly onto your eardrums. And even with protection algorithms, you’ll lose detail, ruin transients, and risk unpleasant, inharmonic distortion.

Overloading your DAW mixer channels will usually just trigger some internal protection algorithms, with the same results as above. (Even the most cheaply made analogue mixers don’t sound great when distorted.)

Plugins are particularly susceptible to bad clipping, especially because it is so easy to not realise it’s happening when running multiple plugins in sequence – each can introduce its own anti-clipping (or actual clipping).

Analogue isn’t immune to bad clipping, either. It can sound really nice, particularly with high-end pre-amps and valves. But even if the recording sounds nice at the time, this is very much a one-way street. You can record clean and introduce analogue clipping later, with precision and control. But once recorded, you cannot later undo that effect.

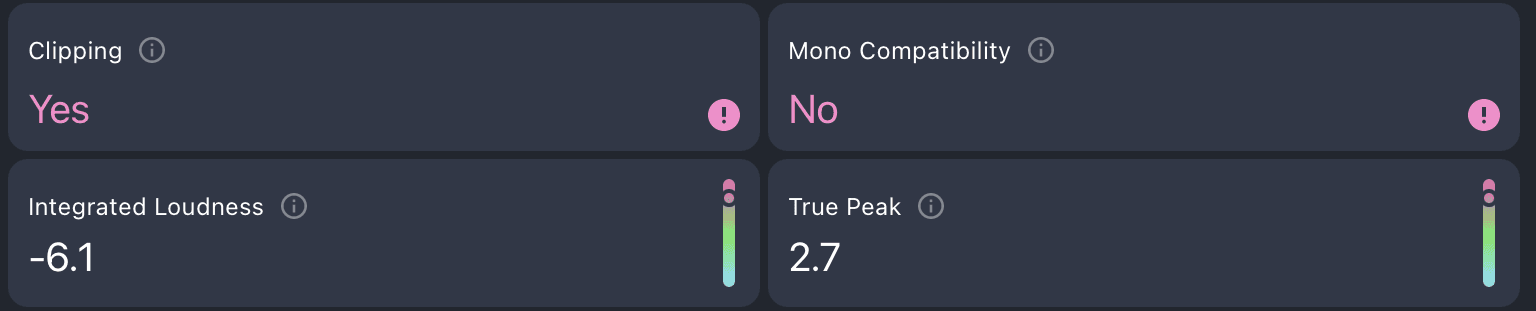

When it comes to clipping issues at the mixdown and mastering stage, Mix Check Studio can help. You can simply upload your master or pre-master, and it will tell you if clipping is occurring and, if so, offer some practical suggestions for dealing with it.

Now, since we’ve already touched on creative clipping...

When clipping is cool

It’s fair to say that bad clipping is clipping that isn’t planned and causes problems we can’t undo. But what about when we do want it?

In analogue systems, clipping can actually introduce some nice effects. Analogue doesn’t have a hard limit of 0dBFS. Peaks are not just sliced off at the top or rendered into a flat ceiling; they’re progressively flattened. And, as we’ve learned, this alters the sound.

Done lightly, particularly through valves or tape, it first adds gentle warmth, also known as saturation.

Push harder, and the signal will start clipping, introducing distortion. For example, by turning up the signal level from an electric guitar before it’s amplified, we create the pleasing distortion that’s defined in a million guitar solos.

And it’s not just guitars. Clipping, in the form of this overdrive/distortion can add character to vocals, synths, drums… anything. And by duplicating a signal and only distorting one copy, you can retain all of the wide dynamics of the original version whilst still enjoying the tonal characteristics of the clipped signal.

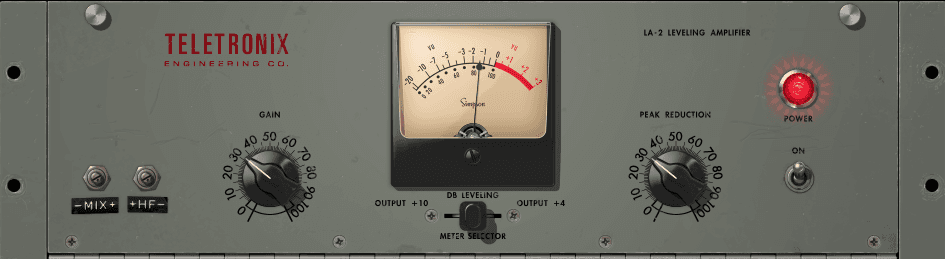

The tonal nature of the distortion varies according to the equipment, but it’s commonly harmonic, related to the frequencies of the audio itself. And there are software plugins designed to simulate exactly this kind of analogue-style clipping behaviour.

In mastering and drum processing, too, clipping can be a great tool. So-called soft clipping is an example of this. Soft clipping operates by starting to attenuate (reduce) the signal earlier, before the highest peak is reached, which can be used to round off transients.

Soft clipping can also be found on some limiters, applied before the main limiting section, which can result in smoother results than brickwall limiting alone (see Dynamic Range Demystified - Coming Soon).

Headroom matters

Returning to bad clipping now, the key to avoiding it is managing our headroom. And headroom is all about the relationship of our audio to our ceiling.

The ceiling in our digital audio system is 0dBFS, the point above which the signal cannot pass. We’re constantly manipulating signals in various ways, and everything we do to the signal has the potential to change the signal level and affect the peaks.

It’s essential, therefore, to leave enough headroom.

All the world’s a gain stage

The simplest way to control headroom is not to add too much gain at your input stage. Or, if the signal is already very loud, to reduce the input level.

Managing your signal level at each part of the process is critical, and it has a name: gain staging.

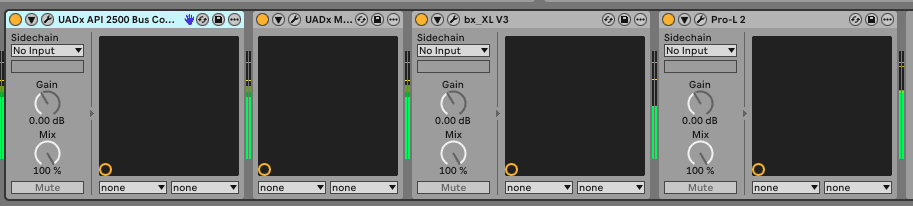

Audio recording, processing, and mixing is done in a series of stages, and every new process – compression, EQ, tape-emulation, etc. – is its own stage with its own input and output. Gain staging is the process of continually tailoring the gain to suit each of them.

The optimal headroom varies. Take recording audio, for example. In digital-only systems, where there is no inherent analogue noise in the system and negligible signal degradation at lower levels, you can technically allow yourself 10dB or even 20dB of headroom, without the audio really suffering.

In analogue paths, however, there is always a certain amount of noise or other electrical artefacts like buzzing or hum. So very quiet signals will start to get lost in the noise. If you record audio with insufficient input gain and later raise it, the unwanted noise of your recording path will also be raised, sometimes making the audio unusable. This is particularly true of recordings made to tape or through analogue pre-amps.

And even in your DAW, most tape emulators and analogue channel strip recreations simulate this noise too. For example, if you play too quiet a signal from a soft synth into either type of plugin, then bounce that channel (i.e. render it as a new audio file with the processing applied), the ratio of noise to synth will be baked into that new audio file.

There aren’t any hard and fast rules, but as a rule of thumb, leave yourself at least 6dB to 10dB of headroom when recording into your DAW. And in analogue systems, try to make sure that the signal path is loud enough that you can’t hear the hiss or noise without turning up the monitoring very loud.

Headroom in mixing

Headroom isn’t just something for individual signal paths, by the way. When mixing, the same thing applies. If you start your mix by setting the level of the kick drum too close to its maximum level, not only will the overall track overload the master bus when you add the rest of the parts, but you will leave yourself no headroom to later raise the kick.

True peak

It’s impossible to discuss clipping without mentioning true peaks. True peaks are a side effect of the way digital systems capture sound. Unlike analogue, which represents real soundwaves with continuous, unbroken waveforms, digital captures soundwaves as a series of snapshots.

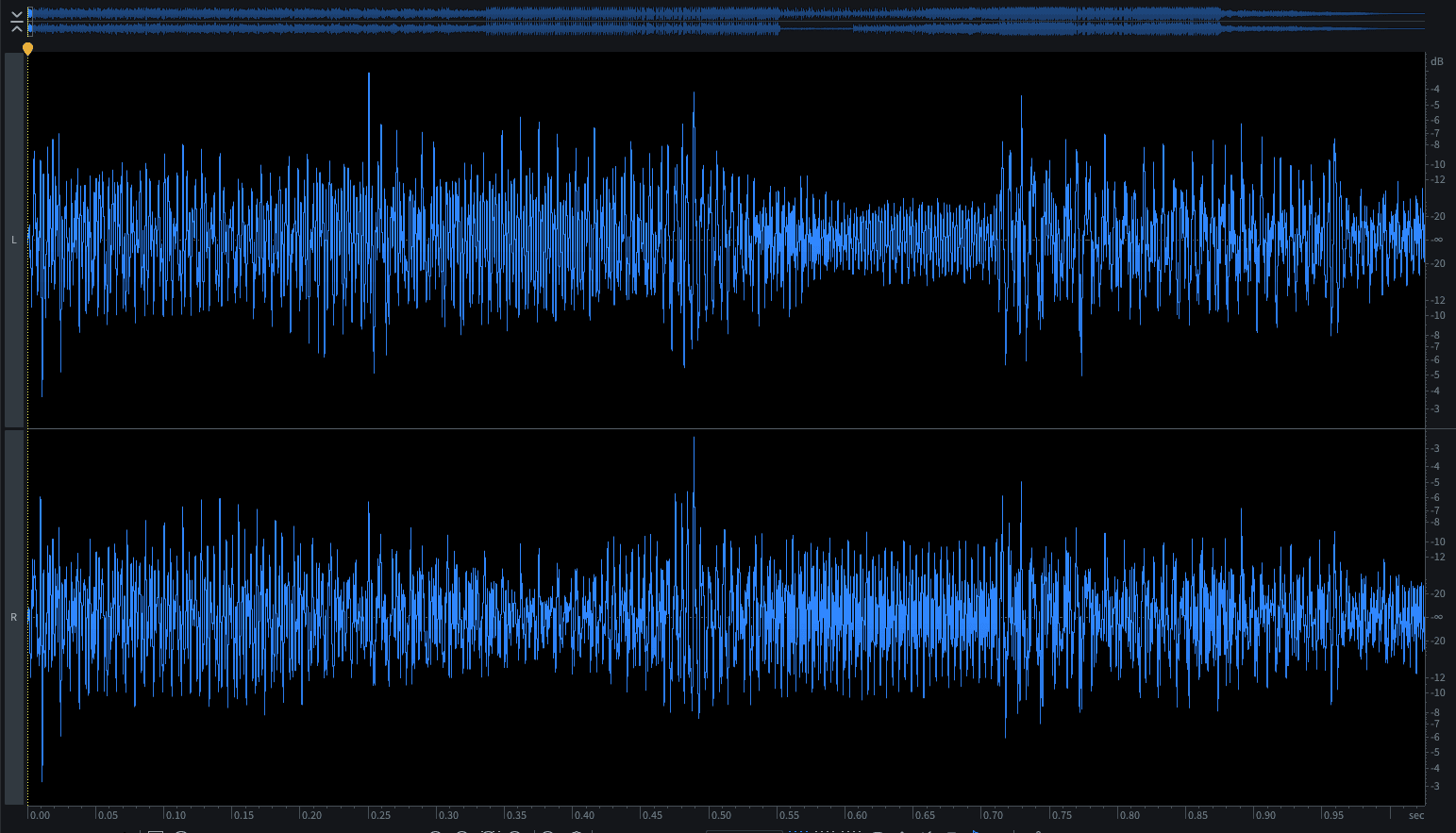

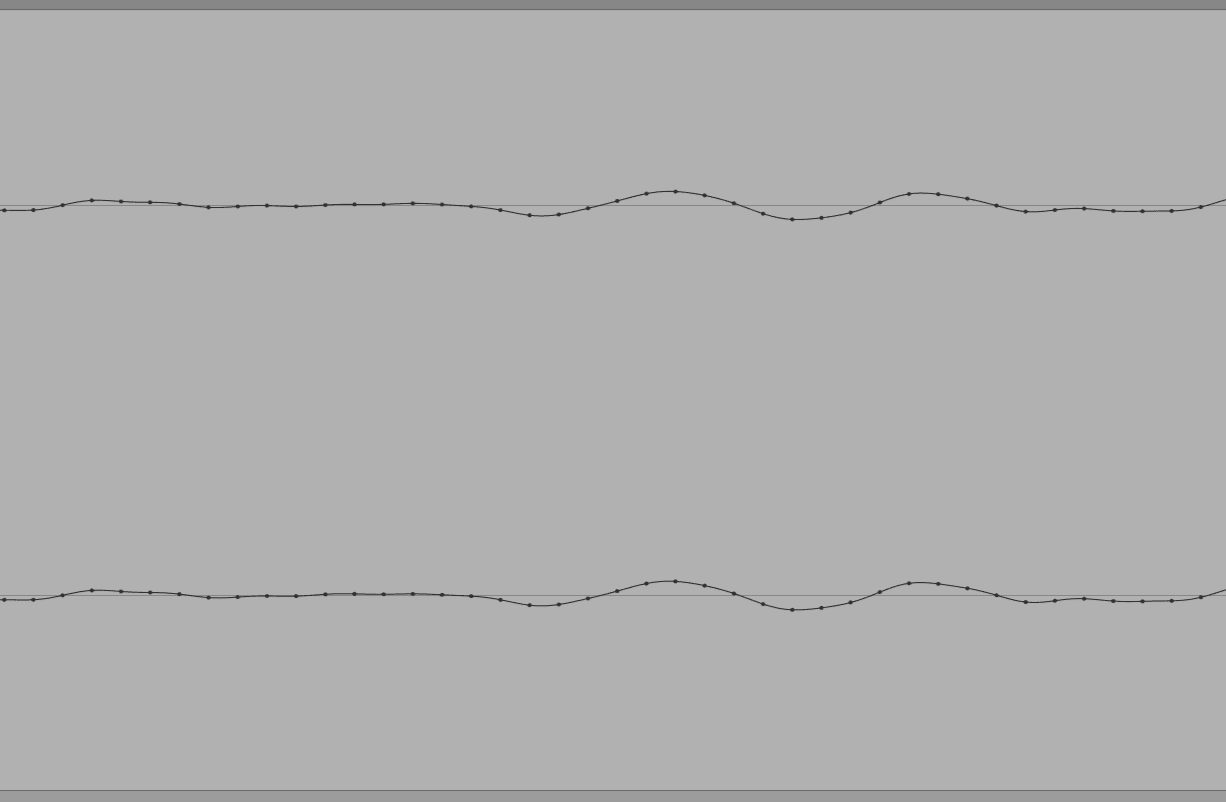

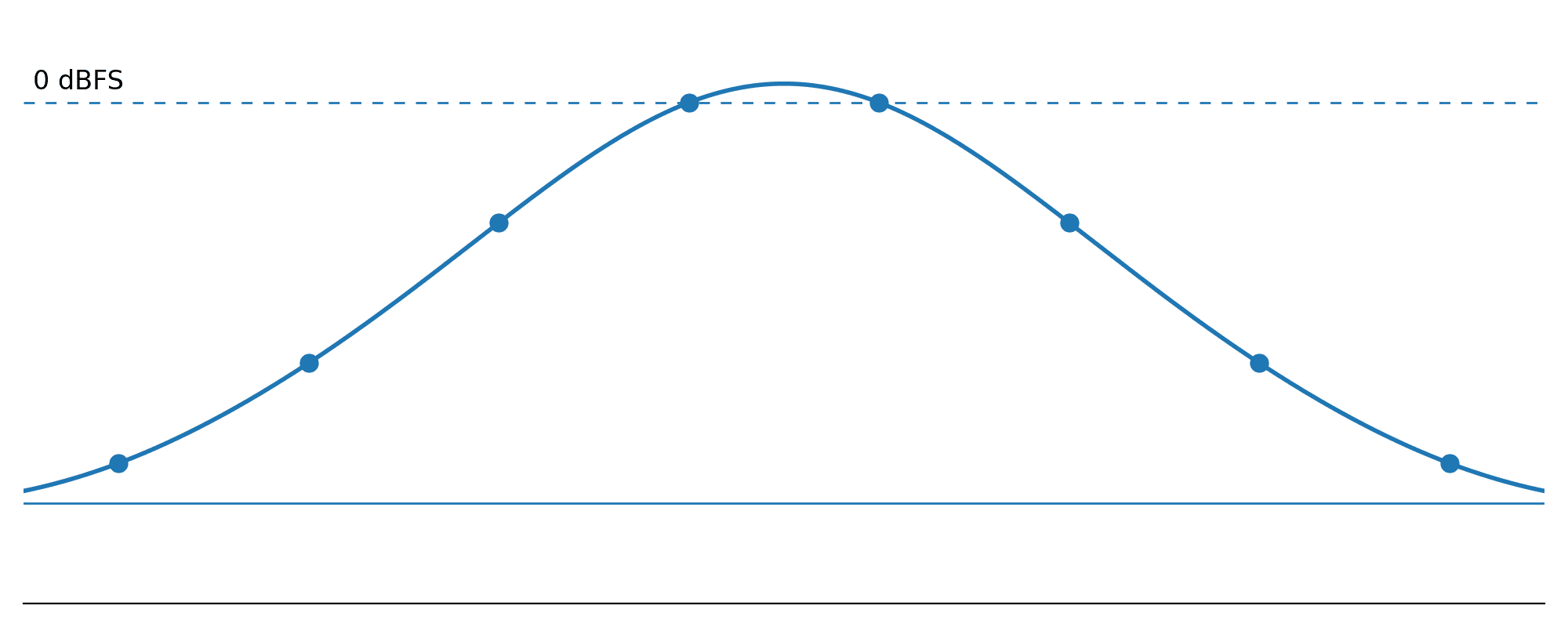

Look at this waveform in Ableton Live.

Each dot represents a single snapshot – they’re points on a graph. The smooth line shown between them doesn’t actually exist in digital audio – it simply shows what you’ll get when the snapshots are converted into a continuous analogue waveform.

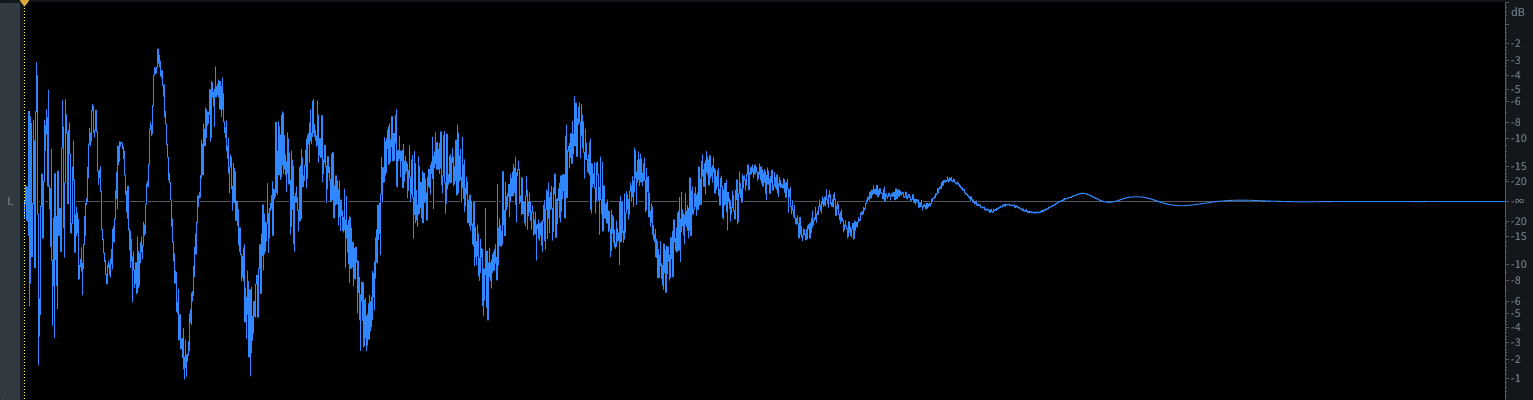

So when our software tells us the peak value for an audio file, it’s really telling us the highest level of dots on a graph. But when they’re converted back into analogue signals, the digital to audio converter has to reconnect those dots. And that’s usually fine. Modern digital brickwall limiters, though, push things much harder. Let’s see what can happen.

Notice the two adjacent samples at 0dBFS, right on the hard limit of digital audio? To convert this into sound, the digital-to-analogue converter must complete the shape of the waveform. But the shape of the waveform will generate a new peak between the two samples. A new inter-sample-peak (ISP) will emerge. This is the ‘true’ peak – the peak that results when digital audio is converted into an analogue signal for playback.

For the most part, the software and hardware we use to produce our music can handle these true peaks without issue, so we don't notice them. But the digital-to-analogue converters in the consumer-level gear our listeners use sometimes cannot and can introduce clipping, especially with frequent and extreme inter-sample peaks.

True peak, then, is a calculation of the real-world peak value, allowing us to compensate in advance, avoiding playback problems.

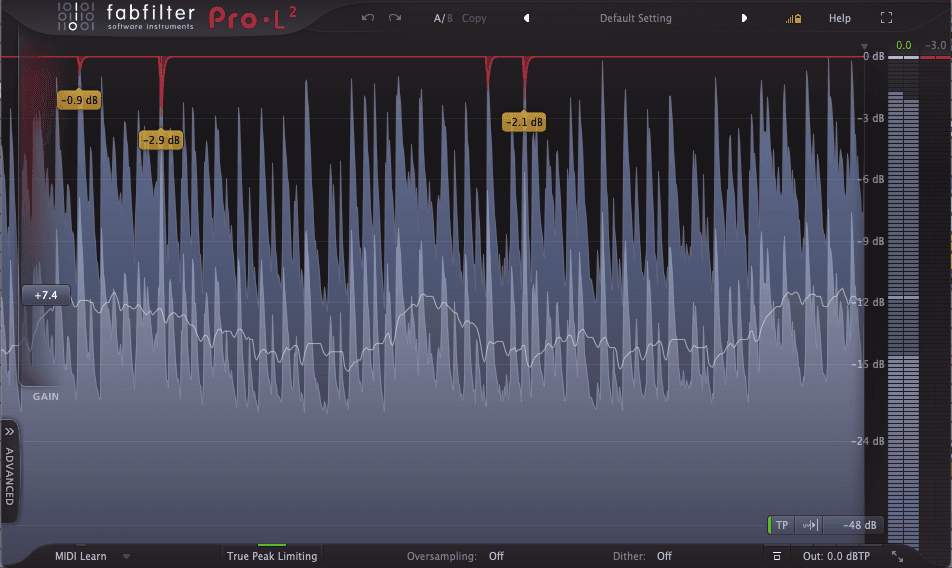

True peak limiters

One solution to true peaks is a true peak limiter. It uses something called oversampling, which increases the resolution of your audio inside the processor, allowing it to spot these true peaks and then limit the signal accordingly.

The main side effect of true peak limiting is that it can soften transients. Dance music producers, for example, can find that the crack and punch of their kicks and snares is heavily impacted by true peak limiting.

Ultimately, the debate rages on in mastering circles – should you use true peak limiting or just keep an eye on true peaks and dial back your conventional digital limiter to minimise them?

But as long as people are streaming and listening to music on consumer digital devices, the relevance of true peaks when mastering is not in question.

Because whatever position you take on true peak limiting, excessive true peaks are problematic and can even lead to streaming platforms adjusting your music for playback.

Analysing your tracks with Mix Check Studio lets you know if your true peaks are excessive, and will offer practical tips for dealing with them.

Final thoughts

So it turns out that clipping is the flawed antihero in our production story. As long as you're working side-by-side towards the same goal, it can add character and energy, help you tame transients, and even rescue a dull vocal or instrumental take.

But don’t turn your back on it for a second. Left to its own mischief, it will ruin recordings, suck you into doom-spiralling bass black holes, wreak havoc with rhythmic energy, and apply a much-unwanted faecal touch to your masters.

Don’t worry, though. You know, clipping’s Kryptonite now, the Achilles’ heel to press every time it goes rogue or sneaks into places it’s not welcome.

Be aware. Watch your levels. Embrace headroom.

Now you’ve read about clipping and headroom, why not read our related articles on dynamics - coming soon and loudness?