A Simple Guide to Loudness and Metering

2026/01/08

For many, ‘loudness’ is the most confusing topic in production – but it needn’t be intimidating. Here’s everything you need to know...

What is ‘loudness’? For now, think of it as how loud one track feels to the listener compared to another played at exactly the same volume setting. Get it wrong and you risk your track being turned down by the likes of Spotify and Apple Music… or clearing a dancefloor! Get it right, and your track will shine wherever people hear it.

Don’t worry, though, it’s not complicated. This article demystifies the key concepts and terms and explains everything you need to get it right. Armed with this information you can then get a free mix analysis from Mix Check Studio to ensure your track plays back perfectly on every sound system and streaming platform.

Mastering, metering, and loudness

Loudness is most commonly discussed in relation to mastering – the process of preparing a track for distribution (via streaming, vinyl, etc.). And a primary role of mastering is achieving optimum loudness.

The key tool for controlling loudness is the limiter, a kind of very specialised, strong dynamics controller. If you’re new to this concept, you should read Dynamic Range Demystified first for an easy-to-grasp introduction.

Now, while limiters control loudness, meters are an essential companion. They’re how we keep track of what our limiter is doing, avoid problems listeners might otherwise encounter, and adhere to stringent specifications for broadcast and streaming.

Let’s look at the things a modern audio meter shows you.

Decibels and dBs and Full Scale – oh my!

The term decibel is used in a number of different audio contexts, and since people often lazily abbreviate them all to dB, it’s good to know the difference.

dB: This is the basic unit for describing changes or differences in either sound or signal level. For example, saying “boost the kick by 1dB” means you want the level of that channel to be 1dB higher than its current level.

dB SPL: When referring to the volume of real-world sound – the pressure of sound waves in the air – we use dB SPL (Sound Pressure Level). This is what local councils measure outside a pub when trying to find excuses to close it down.

dBFS: When we’re talking about digital audio signal levels – the signals inside your DAW or digital hardware – we use dBFS (decibels relative to Full Scale). In digital systems, the maximum value is 0dBFS, with everything else shown as a negative value. So if somebody says ‘your pre-master should be -6dB’, they’re actually saying ‘the highest peaks in your pre-master should be -6dBFS’.

Speaking of peaks…

Peak vs. RMS

From the 1950s right through to the late 2000s, the key considerations in mastering revolved around ‘peak’ and ‘RMS’.

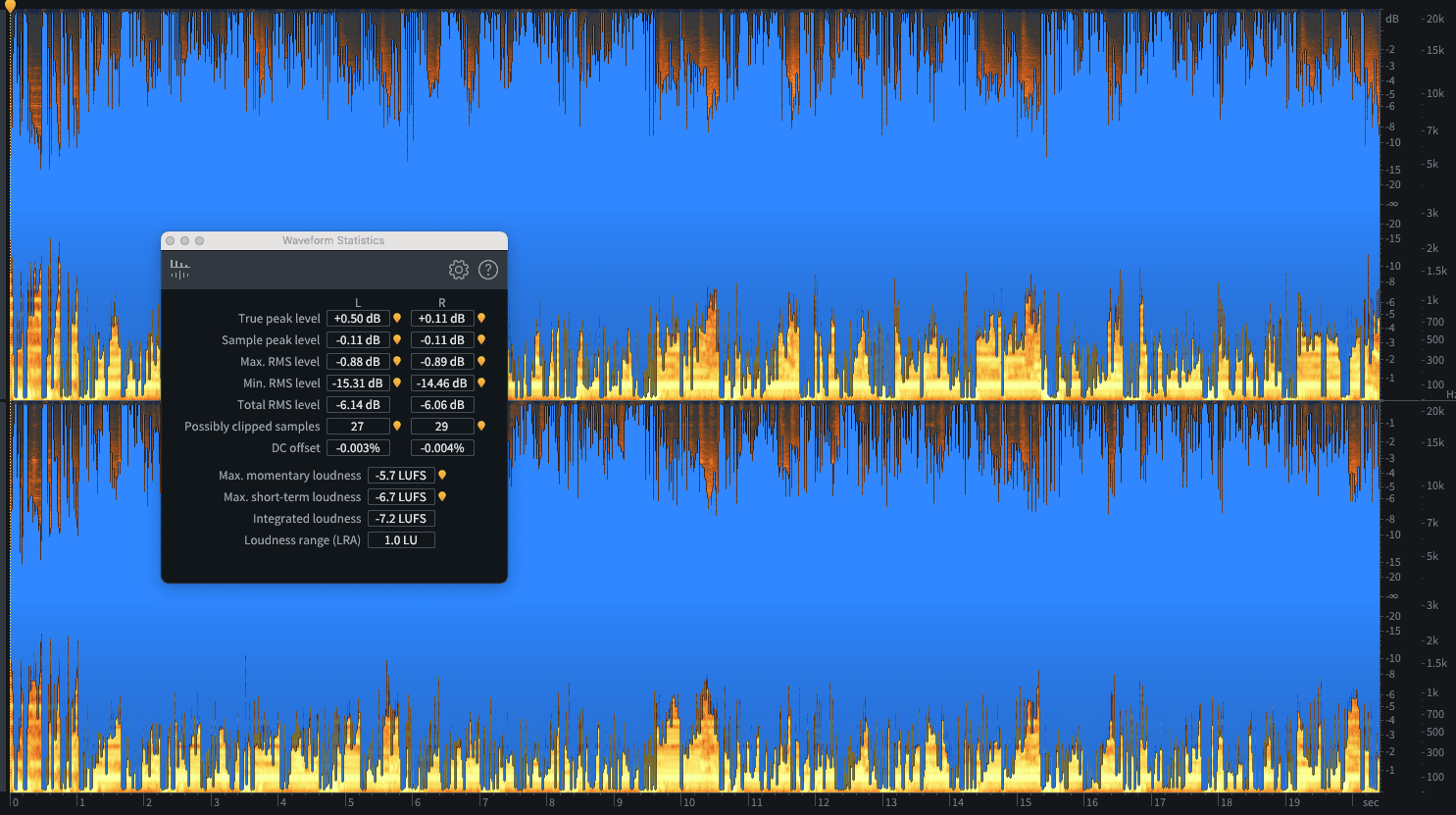

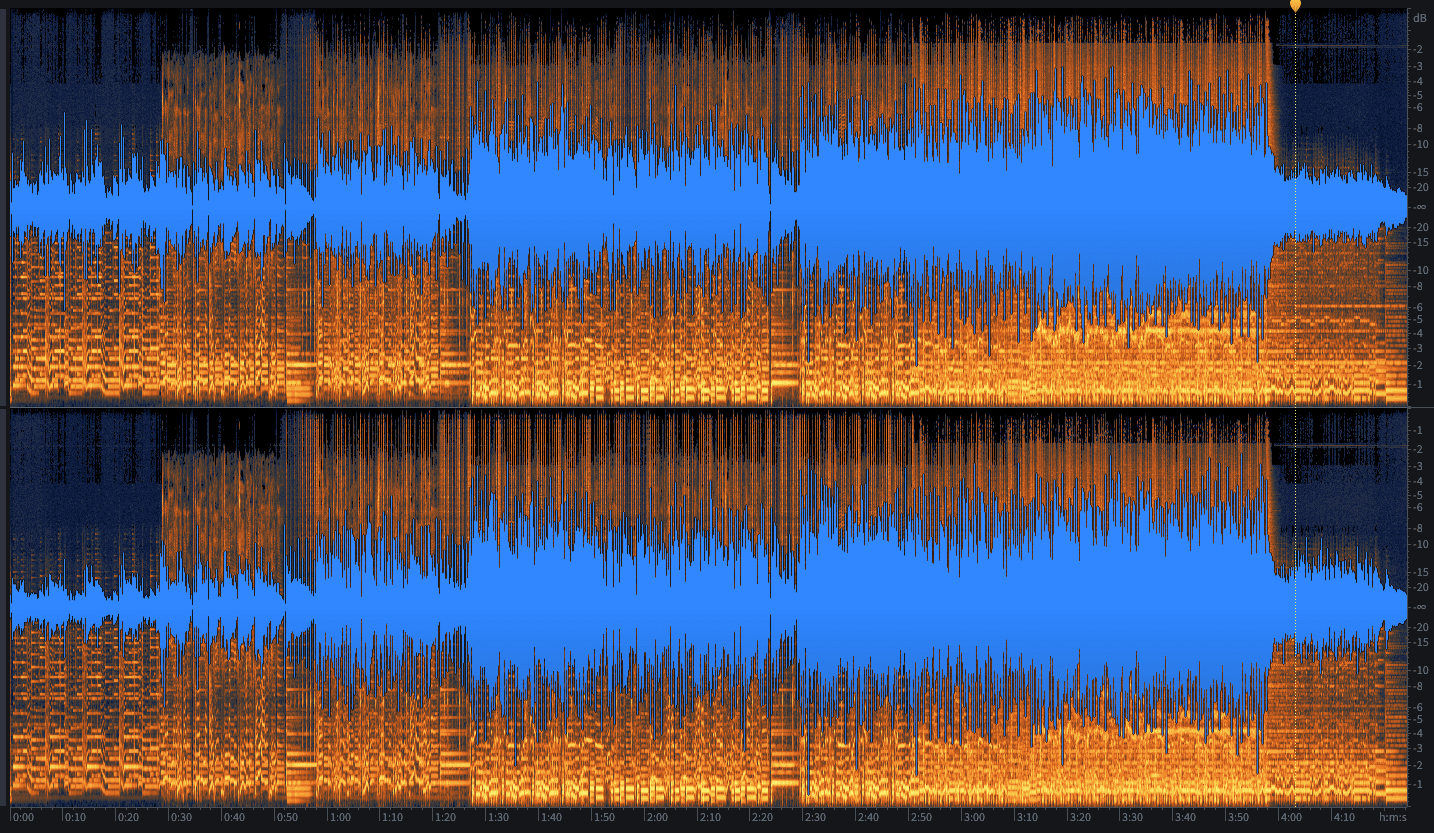

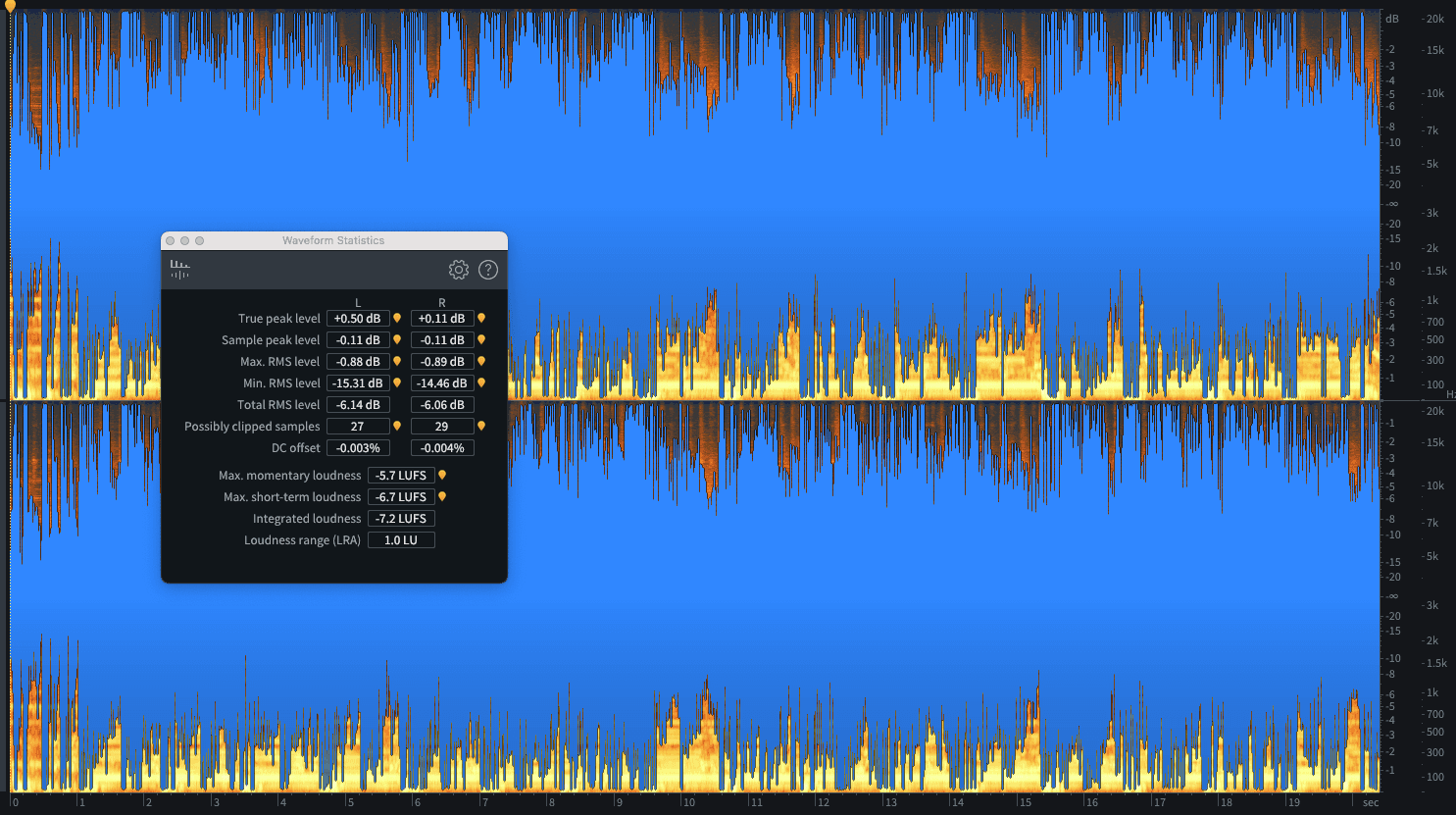

Look at the waveform below.

The peak value is the loudest value it reaches throughout the whole piece of audio – in this case 0dBFS, which it reaches multiple times.

But now look at this file.

This also has a peak value of -0dBFS. But let’s listen…

Example 1: https://on.soundcloud.com/CQcxcgaDv9g0C9mvvS

Example 2: https://on.soundcloud.com/eH8PpwCUhkh3Z60myI

The first has an RMS value of around -10.5dBFS. The second has a much higher RMS value – about -5dBFS – and sounds much louder.

Peak-watching, then, is useful for avoiding unwanted clipping (see clipping article - coming soon), whereas RMS expresses the average level, not the highest. Consequently, RMS is a much better indicator of something we can think of as ‘perceived loudness’.

Perceived loudness

Perceived loudness is exactly what it sounds like: how loud a track feels to the listener in relation to other tracks played at the same volume.

This matters both from a technical level – making sure quiet sounds in a song aren’t too quiet to be heard, for example – and because a certain amount of perceived loudness just sounds better to most humans.

The desirable loudness level is subjective and even varies from genre to genre, era to era, and listener to listener. A club-banger, for example, demands powerful, in-your-face loudness, whereas an acoustic folk performance can be ruined by comparable perceived loudness.

Desirable loudness isn’t always the same as ‘loud’.

In practice, the best thing to do is compare your music to that of the tracks and producers you like in the same genre and, as we’ll see later, our Mix Check Studio can steer you towards the right ballpark for your preferred streaming platform.

Now, while RMS gives a truer idea than peak of how loud something will be, when it comes to mastering and distributing modern music, particularly for streaming, we’re gonna need to learn about LUFS.

First, though…

True peak

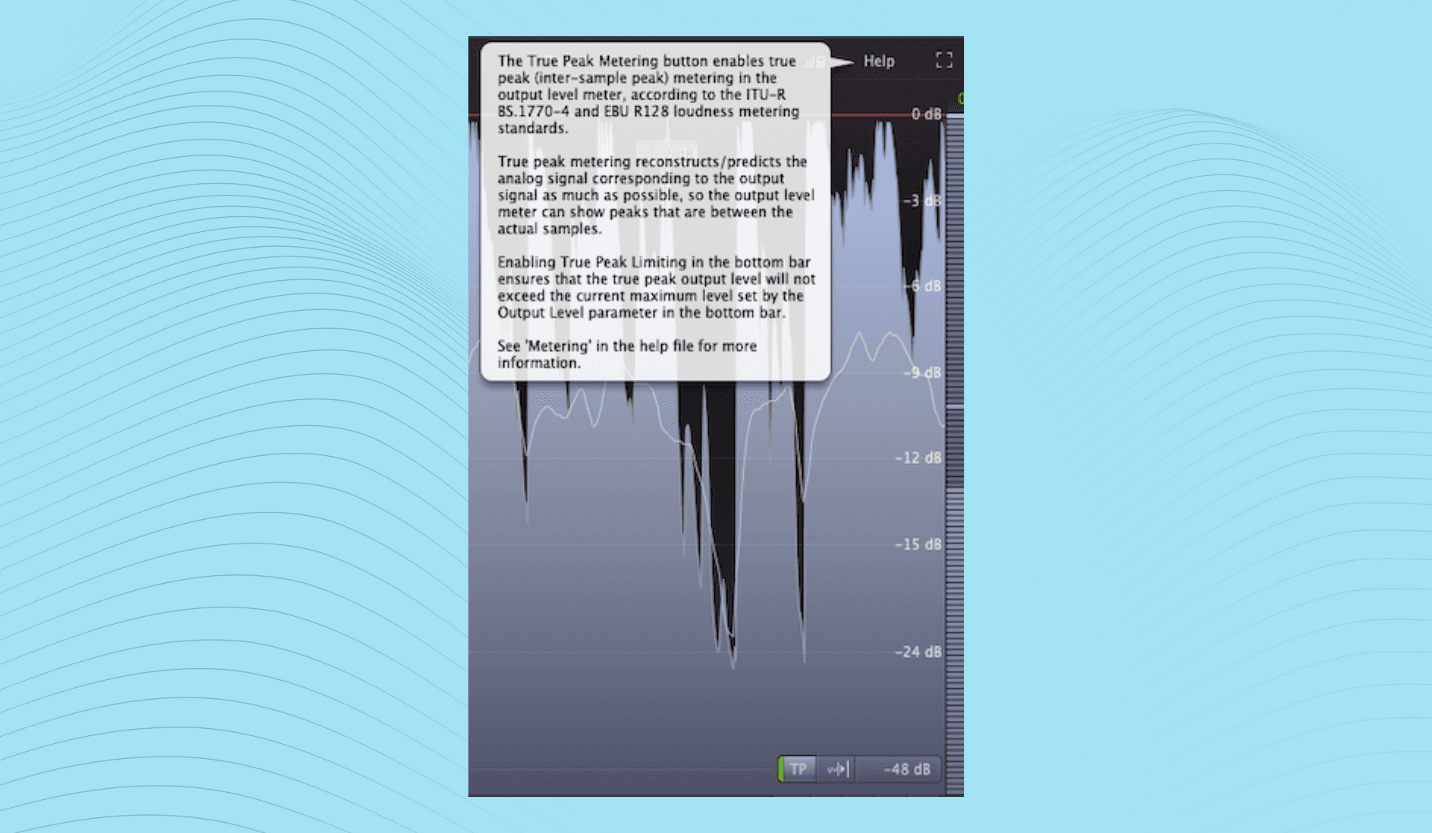

True peak refers to a quirk of digital audio systems whereby the stated peak value of your digital audio file can differ from the actual peak you get when the sound is converted into an audio signal for playback. They occur when pushing digital limiters hard to achieve extra loudness, and though each is only very brief, they can still be problematic.

We explain true peaks in Clipping and Headroom: The Secret to Lively, Dynamic Mixes (coming soon), and they do matter, so be sure to read that too. For now, just be aware that most modern metering systems (and Mix Check Studio) will mention them.

Crest factor

Another term we encounter in audio metering is ‘crest factor’ – the difference between the peak and RMS.

Crest factor varies massively depending on the material, or even the section of a song. Bowed strings have few spikes, so the difference between peak and RMS / average is minimal, but throw on drums, and suddenly it’s much greater. Anything that alters this relationship – limiters, for example – will affect crest factor.

There’s no optimal crest factor range, it shouldn’t dictate decisions. Instead, think of it as a useful way to measure how much you’re changing the dynamics of a track with compression or limiting.

Loudness Range (LRA)

Many meters also display Loudness Range (LRA). LRA is the dynamic range of a track over time – in other words, how much the loudness changes. A very compressed track might have an LRA of only a few dB, while a film score or acoustic recording might have a much wider range.

As with crest factor, LRA helps you keep track of how dynamic your master is.

The loudness war

Before moving to our next, arguably most critical, metering term, let’s shimmy down memory lane to the 2000s – in audio terms, a raging bloodbath of loudness.

Why the 2000s? Look-ahead-enabled, digital brickwall limiters really took off in the 90s, allowing much more extreme limiting… and loudness. This coincided with the shift from vinyl to CD, with the latter’s digital format allowing much greater loudness levels than the analogue product it replaced.

Couple that with a curious human tendency to think louder sounds better in AB comparisons and the industry had a financial incentive to push things as far as the technology suddenly allowed.

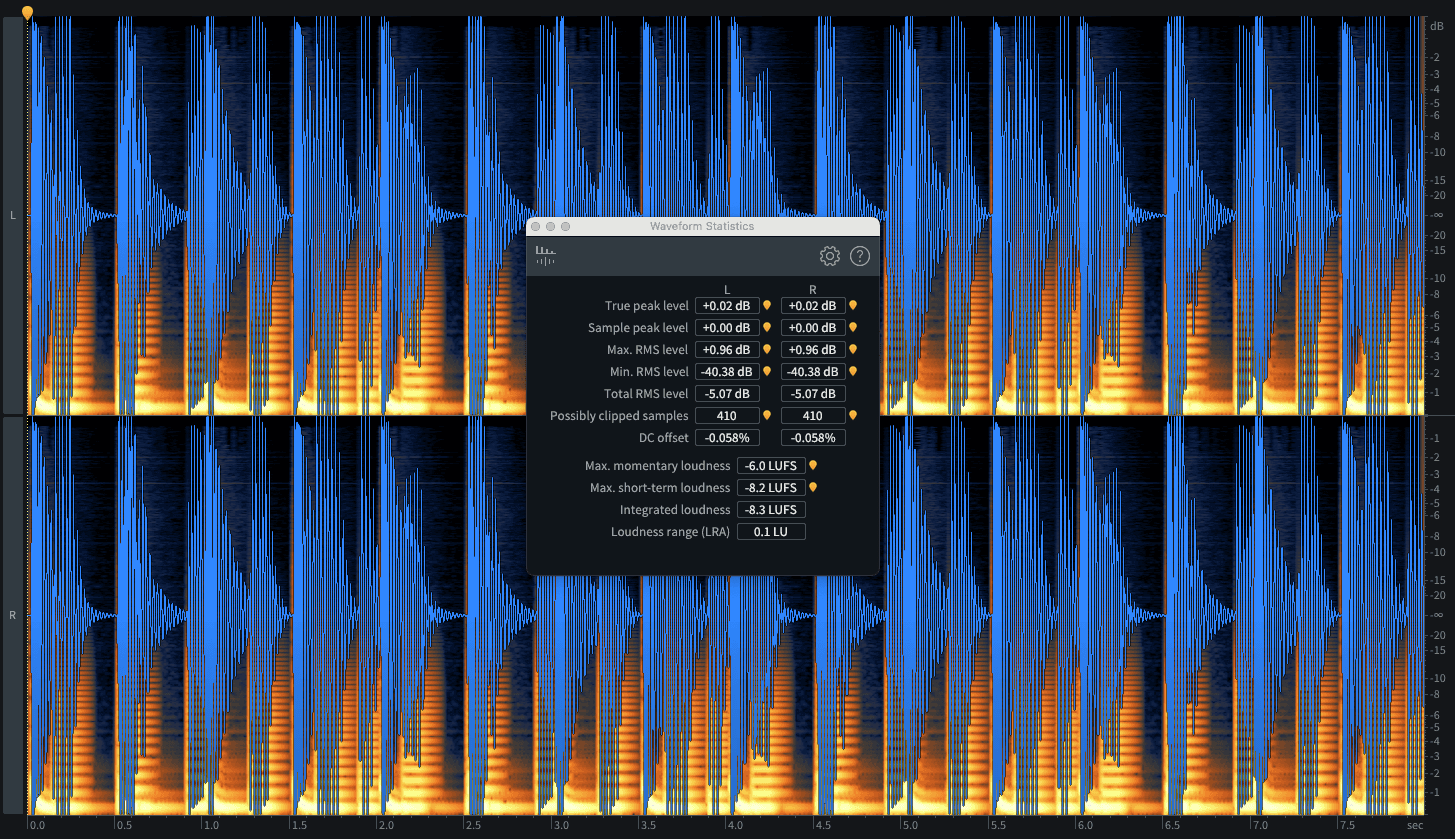

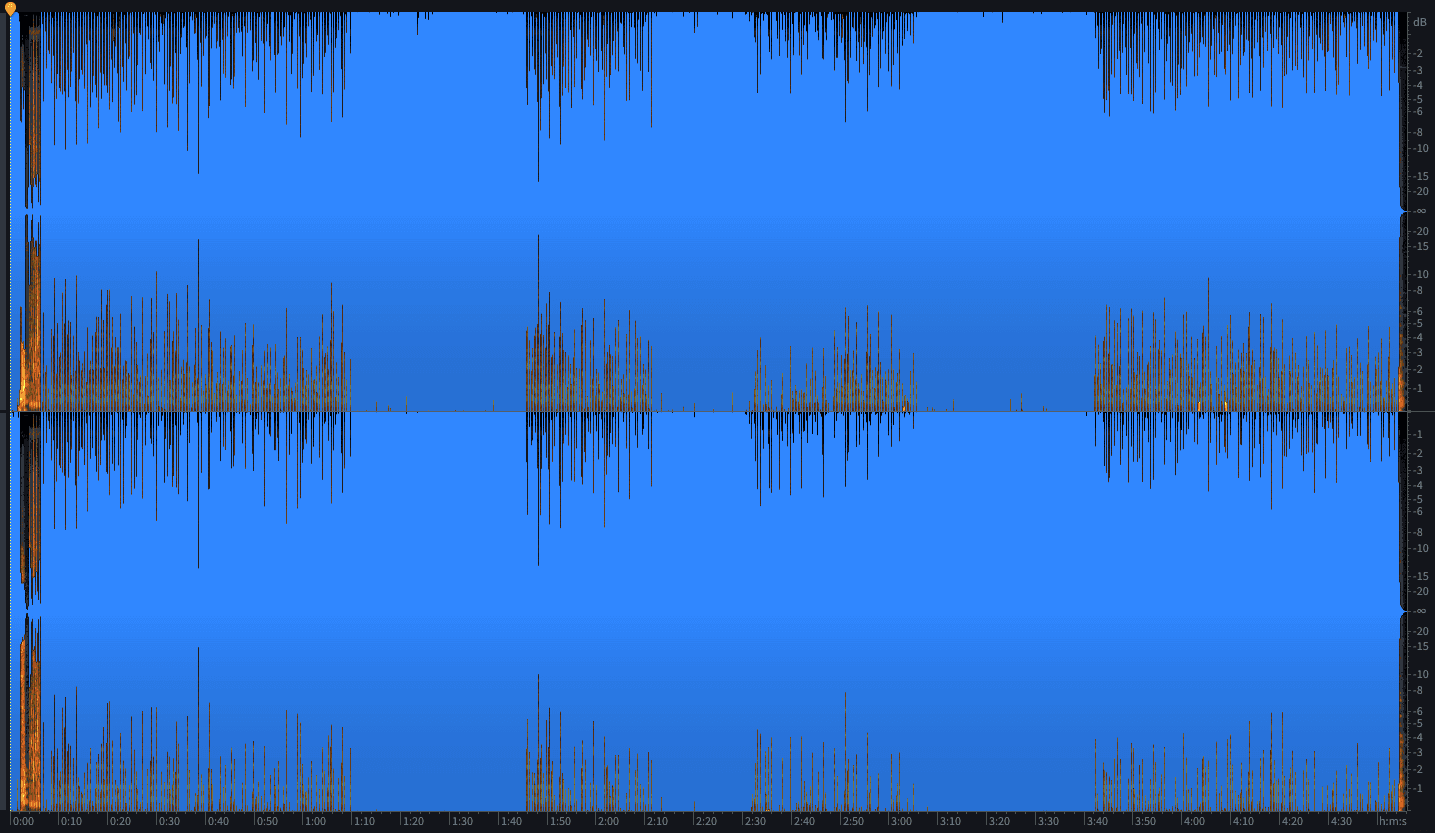

To see how profoundly this spiralled out of control, look at two Red Hot Chili Peppers singles below. One’s from 1991’s Blood Sugar Sex Magik, the other from 2011’s I’m With You.

Crazy, isn’t it? So crazy, in fact, that the broadcast industry stepped in to demand an end to the madness. Enter LUFS.

A brief history of LUFS

Before the noughties, RMS was commonly used as a proxy for ‘perceived loudness’. And if you’re just listening to a little snippet of music in full flow, it’s still a pretty good guide. But RMS has limits (unavoidable pun, sorry).

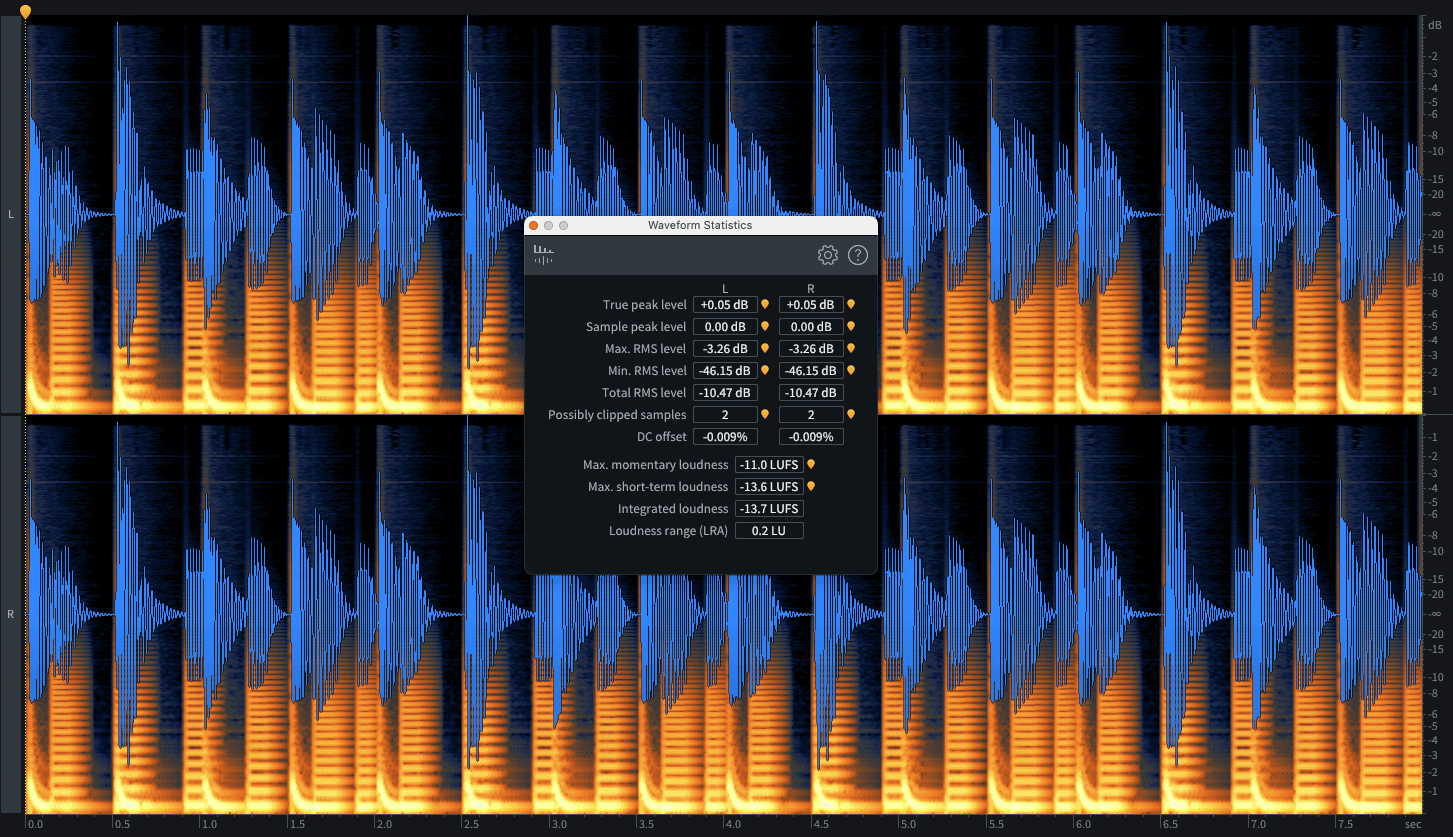

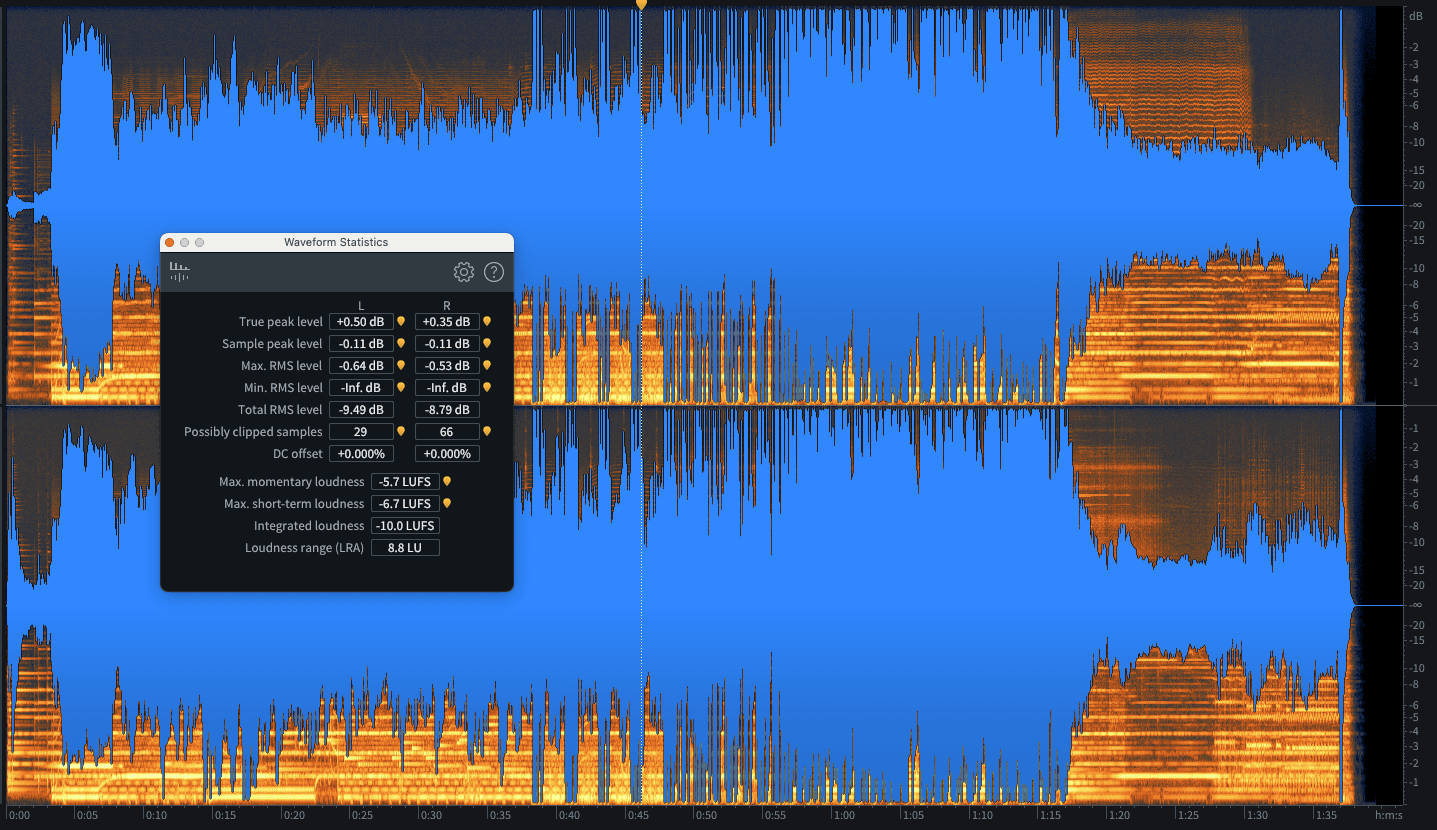

Check out this track.

There are some quiet sections in the arrangement, but an RMS value for a full song doesn’t recognise arrangement decisions – it’s an average value for the whole track, including intros and breakdowns. So the RMS value is around -9dBFS RMS

But let’s crop a loud section and analyse only that.

We get an RMS value of closer to -6dBFS RMS. This is a whole 3dB different but, of course, it is the measurement that matters when considering how loud the whole song will seem to the listener.

It turned out, you see, that in the face of digital limiting, the RMS value of a full song was not a great measure of how loud it would be perceived to be.

A new measurement was needed, and that measurement was Loudness Units relative to Full Scale (LUFS).

Established as a standard in 2006 (with the related broadcast specifications following in 2011), the LUFS system was designed to distinguish between the quiet and loud parts of songs and to calculate the value accordingly.

And it couldn't have come soon enough – particularly, as we’ll see, with the rise of iPods, iTunes, and streaming platforms like Spotify.

Speaking of streaming platforms…

The streaming conundrum

Music streaming has been transformative for loudness and you could argue the music itself has benefited. You see, at the height of the loudness war, the goal was simple: sound louder than the track before.

Usually on radio, but also TV and CD.

But today’s listeners are most likely to hear your music via streaming, and streaming companies want nothing to do with loudness shenanigans. They want listeners to enjoy a smooth, steady experience no matter what track the listener hears next – the antithesis of the loudness wars.

Even Apple’s early iTunes offered auto-levelling, using a proprietary algorithm to work out roughly how loud the track was, then adjusting its level to achieve a constant level from track to track.

And it made sense. Unlike radio, which pre-processes audio for broadcast, a listener with their whole CD collection ripped for shuffled-play on an iPod could be jumping back and forth decades, never mind hopping genres, with predictably huge jumps in perceived loudness.

For the reasons we saw, however, systems balancing song levels based on RMS alone are flawed. They often mismatch levels from one track to the next, and in dynamic systems, can even lead to sudden volume jumps mid-song.

And this is the streaming conundrum. For better or worse, those platforms want you listening to endless, seamless transitions from song to song. And they deploy a peacekeeping army of algorithms to ensure the loudness war ceasefire holds.

For all the sophistication, though, it’s essentially the same kind of process as iTunes’ auto-leveller. The major difference being that instead of measuring RMS or some custom algorithm, they measure LUFS.

And it works very well for the most part – if you try to make your track louder than the one before, you could well find that the platforms simply turn your track down, which can even make it seem quieter than the track before.

Causing jumps to prevent jumps? Huh?

But wait… if the stated aim is a smooth listening experience, and the levelling system can actually make loud tracks sound quieter than less loud ones, why do this?

Firstly, there are some boring technical reasons to punish excessive loudness. For example, almost all platforms employ encoding processes, which can result in clipping with overly loud audio (see Clipping and Headroom: The Secret to Lively Dynamic Mixes - Coming Soon).

But it’s also a deterrent: ‘If you try to restart the loudness war we’ll just turn your stuff down’.

Wherever you stand on the relative merits of the streaming model, the new standards are an indication of the power platforms now enjoy, and it has led to a new era of balance between loudness and dynamics.

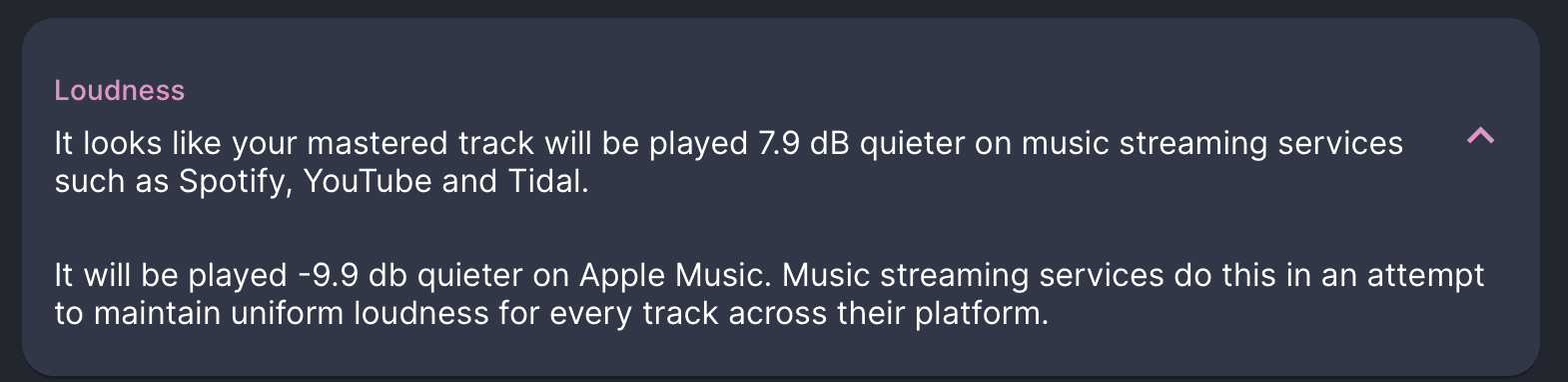

The only snag is that different platforms have different loudness standards. If you’re worried about how to navigate this new landscape, though… don’t. Mix Check Studio offers detailed information about how much each major platform will turn your song up or down.

A tale of three LUFS

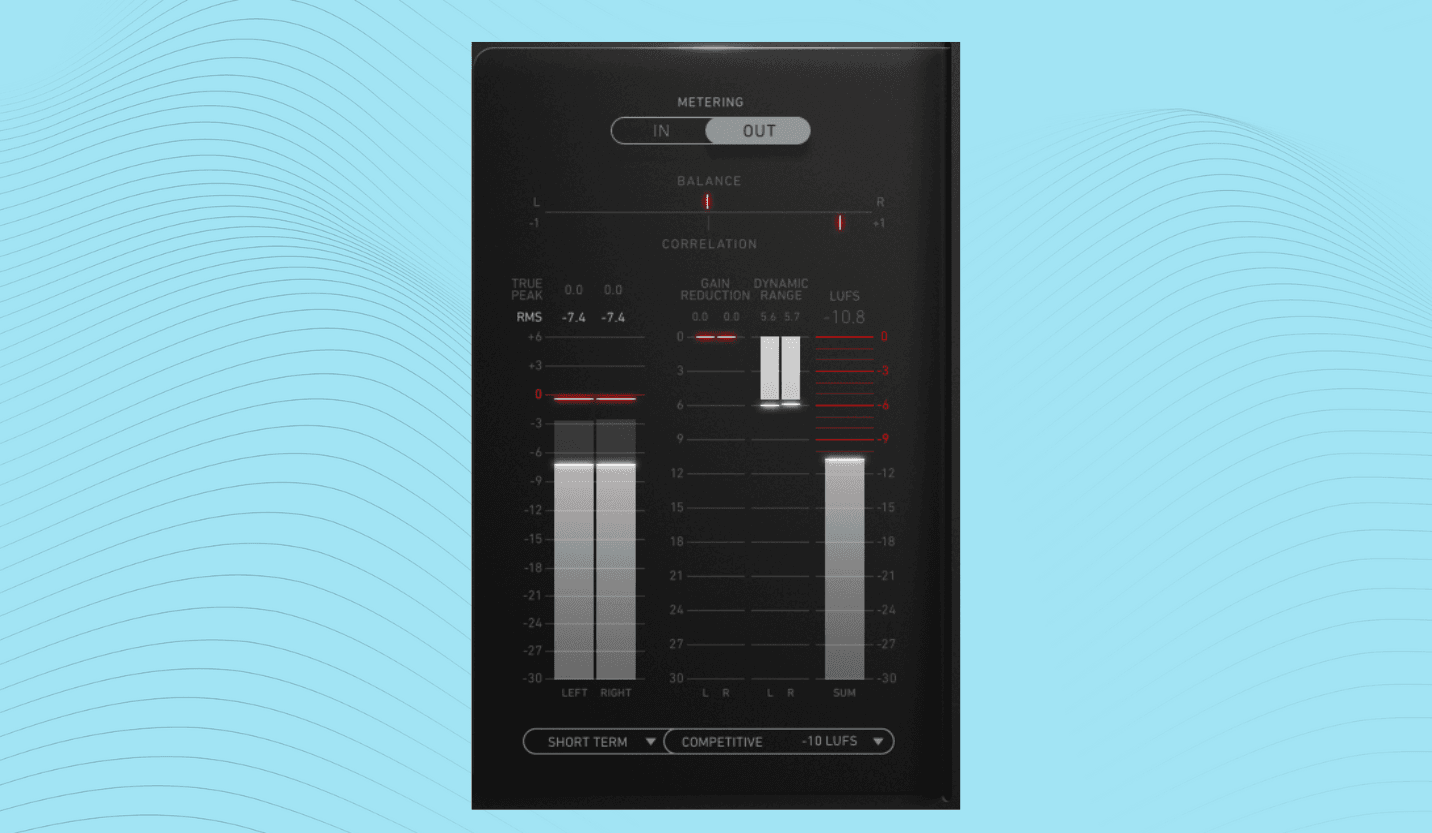

By the way, modern metering often displays three types of LUFS values and it’s worth noting what each is.

Momentary: These measure the signal in overlapping 400ms bursts, delivering a similar reading to RMS.

Short-term: Similar to momentary, but operating with a rolling three-second window.

As with crest factor and LRA, both momentary and short-term can be thought of as useful indicators rather than targets.

Integrated: This is the average value over the whole track. It’s the one broadcasters and streaming platforms are most interested in, so it’s the one you should focus on as a delivery target.

Loudness and RoEx and Mix Check Studio

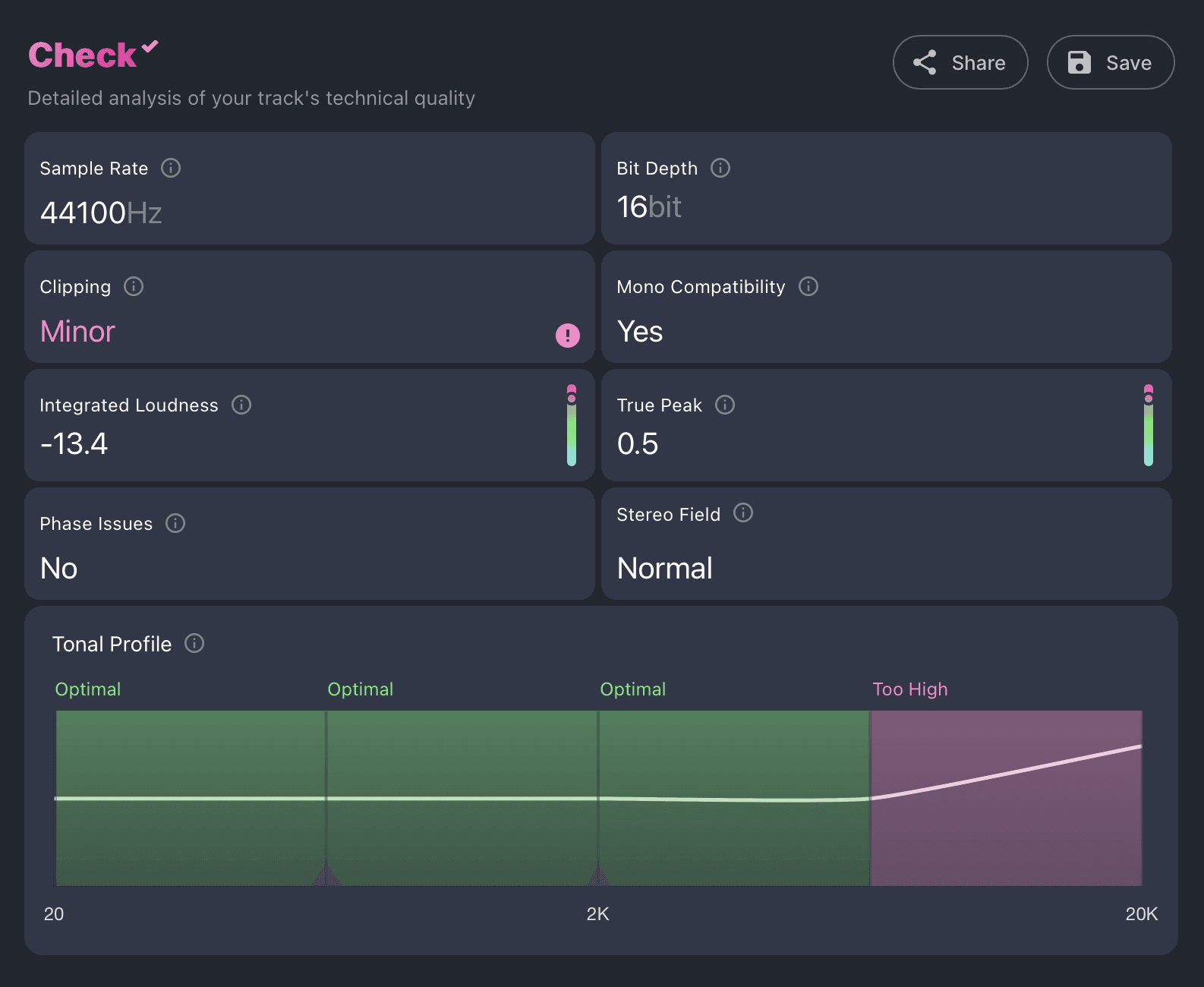

There’s a lot of creative flexibility regarding loudness targets, but also some technical requirements for streaming. Analysing your mix with Mix Check Studio delivers very clear, easy to understand advice.

To run a free check on your track, simply log in with a free account and upload your track. You will then be asked to specify whether your track is mastered or unmastered. Mastered tracks will be much louder than pre-masters so it’s vital to tell the system which your track is.

And if your track is not mastered yet, be sure to remove any limiter you might have added to the master bus before checking with Mix Check Studio (and before sending it for mastering!).

Now select the ‘Check’ option to get a tailored analysis for your track.

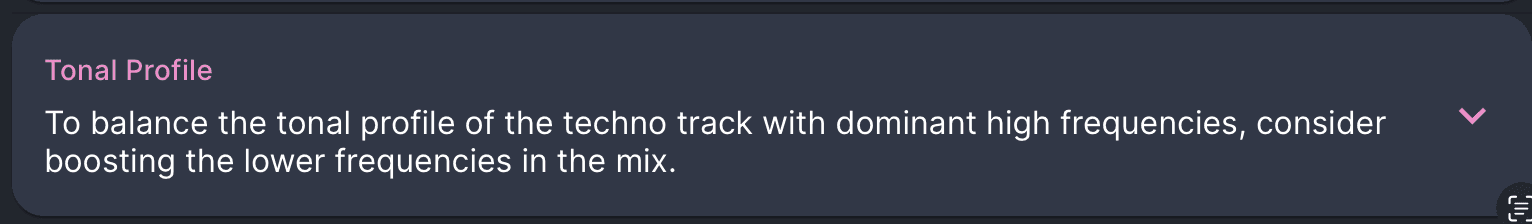

In addition to a variety of tonal, dynamics, and stereo field advice, Roex will give you clear, simple feedback about your track (click the arrow for each to expand it and see the full comment).

By telling you what level adjustments each platform would make to your track in advance, you can adjust the loudness to prevent this, either finding a happy medium for all of them or choosing to tailor your masters to your preferred one.

If your track isn’t mastered yet, Mix Check Studio’s Mastering+ option can do that for you too, making required adjustments to loudness automatically.

It can even create different masters with different loudness, perhaps an extra loud one tailored for club play / Beatport and another for streaming.

Final thoughts

So, what have we learned? Primarily, loudness really matters. Listeners tend to reflexively prefer louder-sounding music, but only when ABing two tracks side by side. Louder is often not better.

Making overly loud masters can seriously degrade the quality of the music, damage the transients, squeeze the life out of things, and even cause your music to sound quieter when people stream it.

Luckily, though, achieving optimal loudness is easier than ever before. Modern digital metering gives you a wide range of tools to keep your loudness in check. And Mix Check Studio takes the guesswork out of things, giving you clear, genre-specific pointers to let your music stand out.